Hydration for Skeptics

The Great Kidney Misconception: Why Your Biology Textbook Got It Wrong

We've all been taught that kidneys are "excretory organs" – fancy biological garbage disposals whose job is to filter waste and produce urine. It's a persistent myth that's about as accurate as calling a master chef's primary role "creating dirty dishes."

Think about it this way: if you walked into a Ferrari factory and focused solely on the metal shavings and waste oil, you'd completely miss the point. The factory's purpose isn't to produce scrap metal – that's just the inevitable byproduct of creating something extraordinary. The same logic applies to your kidneys.

The kidneys don't exist to make urine. That's looking at biology through the wrong end of the telescope. Urine is simply the byproduct – the "metal shavings" if you will – of the kidney's true masterpiece: maintaining your body's perfect internal balance.

The kidney's real job is homeostasis. Every second of every day, these remarkable organs are fine-tuning the precise cocktail of electrolytes, minerals, and fluid levels that keep you alive. They're not waste disposal units; they're master conductors orchestrating the most sophisticated balancing act in biology.

This fundamental misunderstanding of kidney function explains why so many people struggle with electrolyte balance and fluid regulation. When you understand that your kidneys are homeostatic powerhouses rather than simple filters, everything about electrolytes, fluid balance, and mineral metabolism starts to make perfect sense.

Let's dive into how this incredible system really works...

Part 1: The Wildly Underappreciated Science of Fluids, Fatness, and IV Calculators

Introduction: Let’s talk about hydration. Not the Instagram “Stay hydrated, hun!” kind, but the fiddly, facts-and-figures, you-might-have-wanted-a-coffee-first kind. Ignore the wellness clichés and sit back as we untangle what your body’s 42 litres of water really gets up to, why Medscape thinks you’re brimming with H₂O if you’re carrying extra holiday weight, and the real-life wizardry of the potassium-sodium pump (spoiler: it’s not actually a pump you can plug in).

The Body’s Water Map

First, humans are basically a walking, talking water balloon:

A healthy 70kg bloke is around 60% water—that’s 42 litres for free, no plastic bottle required.

Get older or rounder, and the water content falls: babies are plump water balloons at around 70%, elderly folks are shriveling raisins at about 50%, and body fat is the Sahara at just 10%. Muscles, in contrast, are about 75% water—another reason all that steak on keto makes you less likely to dry out.

Where’s All That Water Hiding?

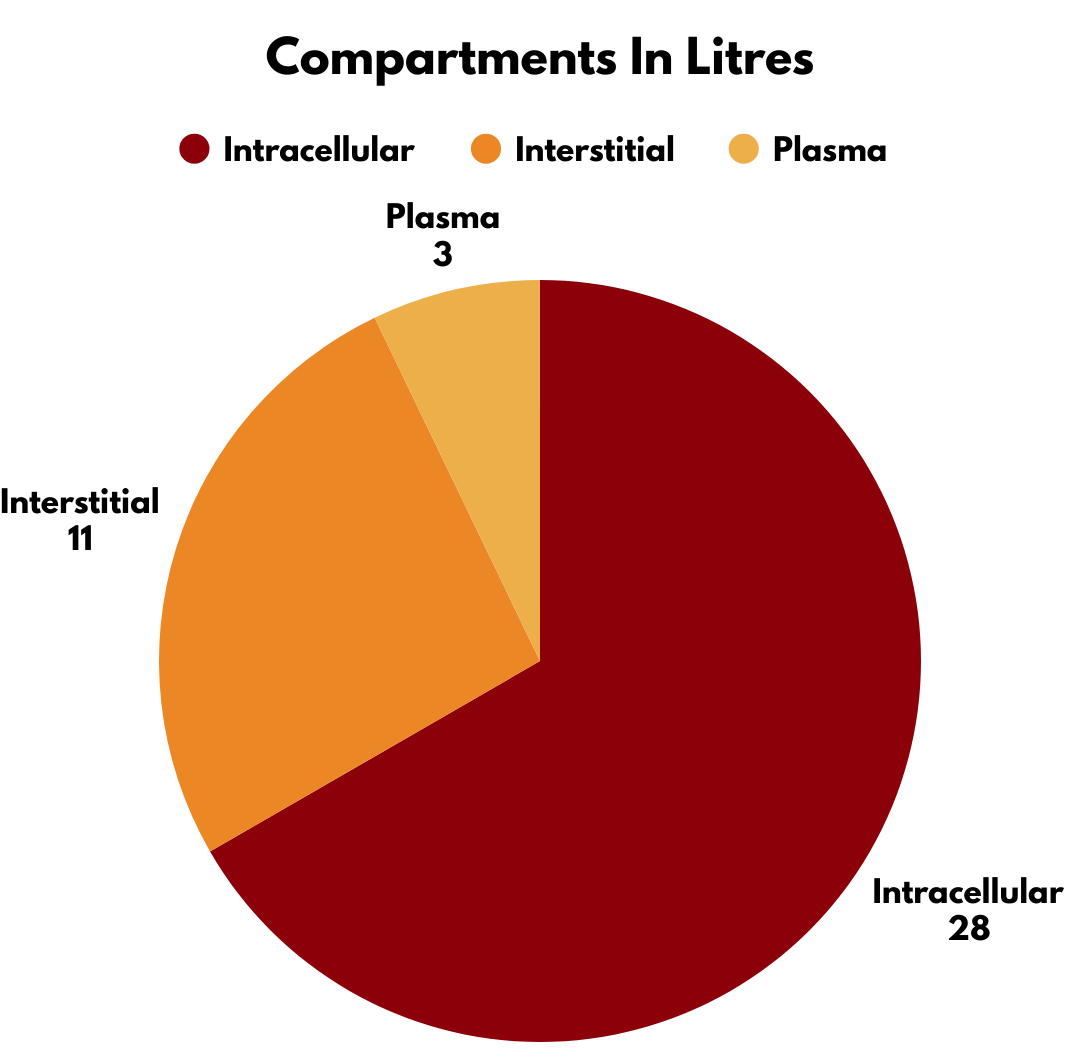

Two-thirds of it is inside your cells (the intracellular compartment: 28 litres for our standard man).

One-third is outside the cells (the extracellular compartment: 14 litres), split into:

Interstitial fluid: Bathing your cells (11 litres).

Plasma: The part doctors like to get out and analyse (3 litres). Plasma is not “blood”—it’s blood minus all the red/white cells and platelets.

Why the fuss? Your body treats its water like VIP tickets: every drop is accounted for, and who gets one depends on their cellular clout.

Osmosis and Diffusion: The Physics Behind the Magic

Before we dive deeper into IV fluids and why some make you swell like a water balloon while others barely register, let's get our heads around the two fundamental forces that move water and particles around your body: osmosis and diffusion.

Think of them as the universe's way of being obsessively tidy—everything must be evenly distributed, and physics will not rest until balance is achieved.

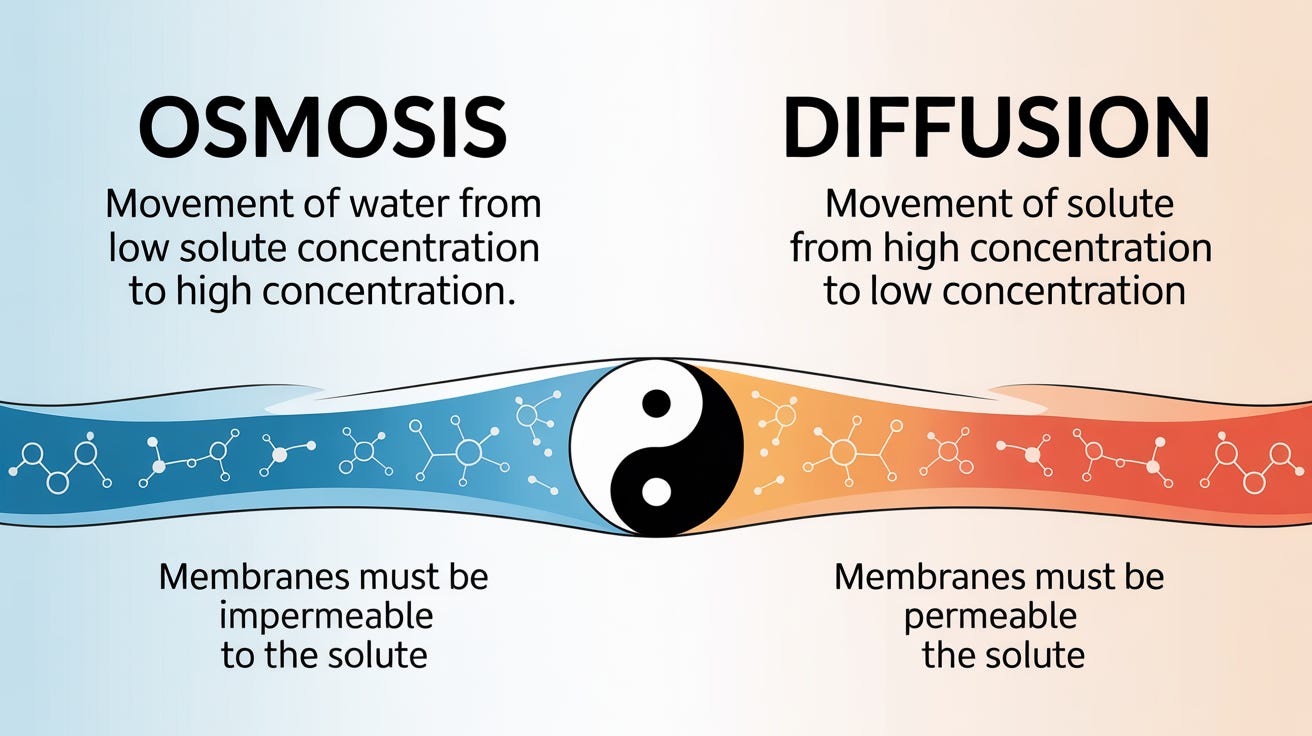

Osmosis: Water's Migration Instinct

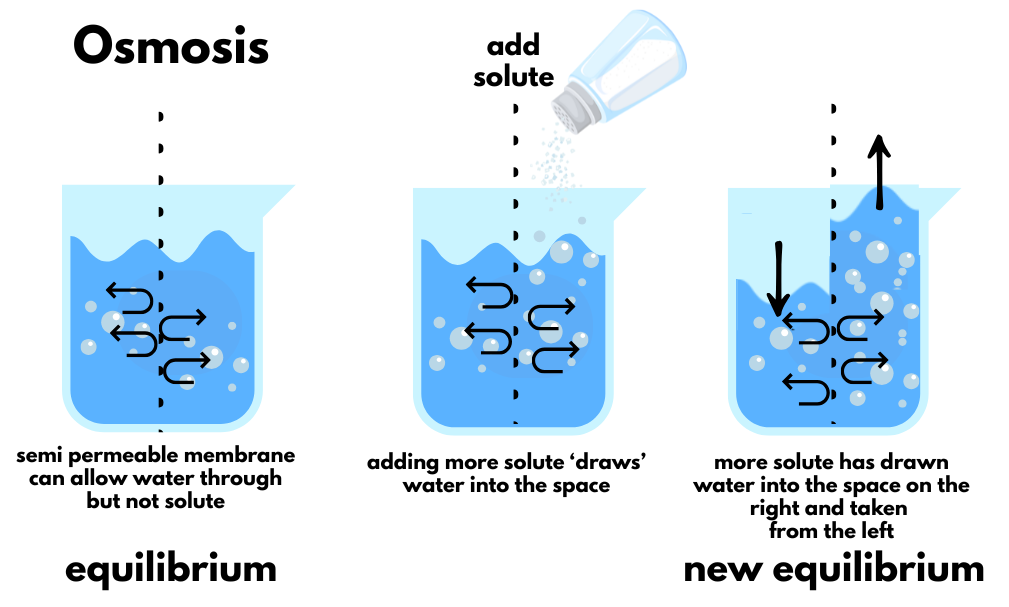

Osmosis is water's irresistible urge to dilute concentrated solutions. Picture a beaker divided by a semipermeable membrane (fancy speak for "lets water through but blocks bigger stuff"). Start with equal water levels on both sides. Now dump salt on one side. The salt can't cross the membrane, but water can—and will.

Water moves from the less salty side to the more salty side, not out of charity, but because physics demands equal saltiness everywhere. The water level rises on the salty side until the concentrations match. It's like a microscopic game of musical chairs where water keeps moving until everyone gets an equal share of salt.

Real-world example: When you accidentally inject hypertonic saline into tissue (don't ask how I know this), the surrounding water gets hoovered into that area faster than you can say "tissue swelling." The tissue becomes a water magnet until equilibrium is restored.

Diffusion: The Particle Shuffle

Diffusion is different—it's about the particles themselves moving to spread out evenly. Same beaker setup, but this time the membrane lets everything through. High concentration of particles on the left, low on the right. The particles themselves migrate from crowded to spacious until they're evenly distributed. No net water movement needed—the particles do the traveling.

Think of it like a crowded pub at closing time: everyone naturally spreads out to less crowded areas until the density is roughly the same everywhere.

Why This Matters for Your Body (And IV Bags)

Your cell membranes are the ultimate selective bouncers:

Water? "Come right in, mate."

Sodium and potassium? "Not without proper ID" (sodium-potassium pump required).

Large proteins? "Absolutely not."

Meanwhile, your capillary walls are more like airport security—they'll let most small stuff through (sodium, potassium, water) but block the big players (albumin, blood cells).

This is why isotonic solutions (same saltiness as your blood) don't cause cells to shrink or explode, hypotonic solutions (less salty) make cells swell like water balloons, and hypertonic solutions (saltier) turn cells into raisins.

The IV Connection

When designing IV fluids, you're essentially playing a game of osmotic chess. Want the fluid to stay in blood vessels? Add large molecules that can't escape (like albumin). Want it to distribute throughout the body? Use isotonic solutions. Want to sneak water into cells without causing immediate chaos? Use glucose that gets metabolized, leaving behind water that redistributes naturally.

It's not just about the total amount of fluid—it's about where physics decides that fluid should end up.

Barriers to Entry: The Membrane Club Rules

Cell membrane: Between intra- and extracellular compartments. It’s a highly selective bouncer: water and small nonpolar molecules stroll in and out, but charged ions—think sodium, potassium—need a special pass via “sodium-potassium ATPase” pumps.

Capillary wall: Divides plasma from the interstitial fluid. Less snooty: it lets sodium, potassium, water, and nonpolar molecules cruise by, but blocks big proteins (albumin, clotting factors) and ALL blood cells.

No one likes a gatecrasher: Albumin hangs out in plasma for this very reason. Meanwhile, water crosses every barrier. This means your plasma, interstitial fluid, cerebrospinal fluid, and even gallbladder juice end up with basically the same osmolality. (Foot fluid = brain fluid. Yes, really.)

Exceptions:

Semen is hypertonic (saltier than the rest of you… for sperm preservation and motility—think of it as the difference between a hotel pool and the Dead Sea).

Genitourinary (GU) tract: From the tip of the Loop of Henle to the toilet, the lining is impervious to water—unless antidiuretic hormone unlocks the gate, allowing urine concentration to be dialed up or down to suit your hydration status. GU = “genitourinary”—your kidneys, ureters, and bladder. Handy for anyone finishing the crossword at the doctor’s office.

The Sodium Potassium ATPase: Biology’s Bouncer

This heroic “pump” is on every cell, hurling sodium out and dragging potassium in.

Simple explanation: It keeps sodium high outside cells and potassium high inside.

Why is this good? It’s like a charged battery: the separation creates an electrical gradient for nerve signals, muscle contraction, and, let’s face it, stopping you from dissolving into soup.

But is there infinite sodium to pump out? No, but the system is dynamic—sodium trickles back in (leak channels, food, etc.) while the pump keeps restoring the balance. You'll never end up with all sodium outside and potassium locked inside—cell membranes always have some leaks and active transports, keeping the concentration gradient alive.

Typical numbers for reference:

Sodium (Na⁺): ~142 mmol/L extracellular, 10 mmol/L intracellular

Potassium (K⁺): ~4 mmol/L extracellular, 140 mmol/L intracellular

Albumin and proteins: Only in plasma—not interstitial fluid

Errors in the Matrix: Calculating Water and IV Fluids

Here’s where the rubber glove meets the cannula. Clinicians use your body weight to estimate total body water—and for the standard 70kg adult that’s 60% (42 litres). But… if you add 30kg of pure fat (with its sad 10% water content), you only gain 3 litres of extra water, not 18. Medscape’s IV calculator, however, will merrily treat your new 100kg self as containing 60 litres of water—off by a thirst-inducing 33%. This can lead to over- or under-correcting fluids and electrolytes during treatment.

Summary of compartments:

Intracellular: 28 litres

Interstitial: 11 litres

Plasma: 3 litres

Why Does This All Matter?

Because hydration is about where the water is, not just how much you glug from a bottle after leg day. The size of your body’s fluid compartments depends on the number of particles (osmoles) they’re holding—not just raw volume. This is the key to understanding why “proper” hydration is so individual, why “bloating” is more than one too many burgers, and why miscalculations in fluid figures can land you on the wrong side of an IV.

Next time:

We’ll expose what “isotonic”, “hypotonic”, and “hypertonic” really mean when choosing an IV solution, and why leaking sodium into the wrong spot can make your brain swell (yes, really).

For now: raise your water (in a glass bottle) in a salute to the sodium-potassium ATPase—the unsung hero in every cell keeping your physiology from becoming a soggy mess.

Conclusion: In summary, your body is a marvel of fluid accounting—47 varieties of membrane gating, electrochemical gradients, and enough maths to keep most doctors up at night with a calculator in one hand and a mug in the other. Next time you see someone say “just drink more water”, you can smile knowingly and ask, “Which compartment?”